a photograph is all that lasts long

with glory years and quiet fears gone

when summer days are far away

you can dream of skies and lover’s eyes

blue

Shoecraft, Eyes, Blue

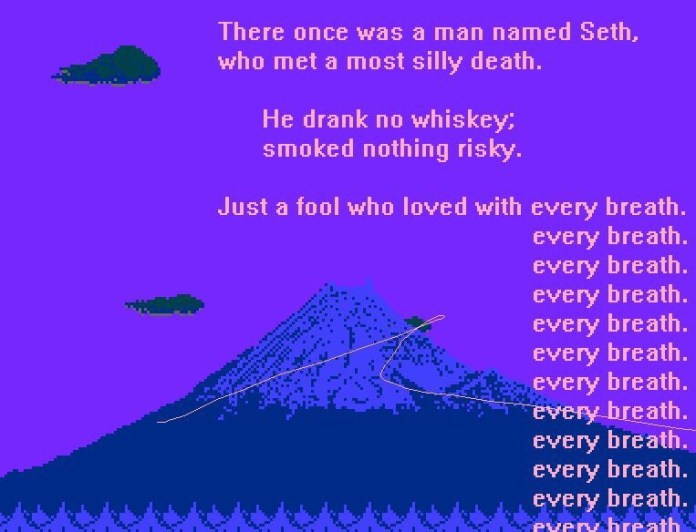

OF all the addictions that may plague a man, an addiction to love is the trickiest addiction to have. This is due to the singular fact that one can not buy love in the marketplace. If one could, that would be another matter entirely and we would not be having this conversation for I would be in the marketplace but we are, and I’m not, for it is — truly, insufferably — priceless.

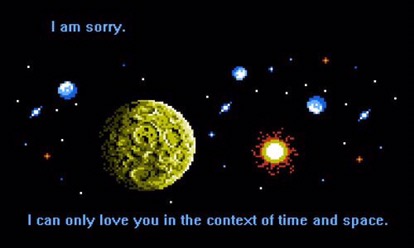

Its effects are astounding. It can take a boy of fifteen — a promising young lad with a first-rate mind and sound disposition — and render him anaesthetised to worldly pursuits. The worlds of commerce and politics and sport are forever more left grey and drab to him. The gold stars of society no longer mean anything to him. He has glimpsed a world drenched in colour and he can not thrive without it. Over the years, he secretly feeds his addiction with scraps of poetry and ancient Persian treatises on Sufism. He devours literature with an unslakable thirst, searching, ever searching. He sees something he can not articulate in the way the sun sets behind lonely apartment complexes. Something beckons to him on the sea breeze as it blows through banyans in the hot afternoons. And something tightens in his chest every night as he watches the rising of the stars from the roof of his ancestral home. Everything he writes ends the same way: smeared with the half-remembered colours of forgotten love. Like waking from a dream and scrambling to put it all down before it’s lost to the aether; knowing it’s going, knowing it’s gone, knowing even as you begin to write that it’s useless and yet still grasping for another fix, you addict, happy in your addiction, wouldn’t trade it for the world because you’d rather your half-remembered colour than the grey, grey, grey of everyone and everything else…

There is a boy or a girl a thousand years hence on another planet who is reading all this, feeling all this. Here, Earth is merely a byword for an unspeakable nostalgia. I write to you — future-boy, future-girl — from your ancestral home. The colours are real. They exist. There is only one way to find them and there always has been. Good luck. Godspeed.

Gharo, Sindh, Pakistan. PHOTO CREDITS: HASHAM MASOOD, M.B.B.S., BATCH XVIII

Gharo, Sindh, Pakistan. PHOTO CREDITS: HASHAM MASOOD, M.B.B.S., BATCH XVIII