hold it in

now let’s go dancing

I do believe

we’re only passing through

Ben Howard, Time Is Dancing

THAT summer we were in the ED together. Patients poured in until every room, every wall, every hallway was packed. But it was good. We worked hard through the hot days, ministering to the masses, until every cough, every fever, every errant heartbeat was beaten into submission. We were young; we thought we could cure the world. And, often, we did. It was that kind of summer.

There were more of us there, of course, but, for me, there was only her. After work, she’d invite me back to her place, just a couple of floors down from mine. We were poor residents, living in the broken mid-century monstrosity across from the hospital in Uptown. We wouldn’t even change, just sprawl onto her IKEA couch in our filthy scrubs, nursing our battered bodies on each other. We never kissed; it was more intimate than that. We held each other, softly, fiercely, breathing in sweat and last night’s shampoo and shards of our souls. Or whatever was left of them after a year of emergency medicine. We watched movies together, too. Shitty ones. Always horror flicks, somehow. Arms wrapped around every inch of skin, hungry for something soft and warm after the beating we’d taken in the ED. Once, during a jump-scare, she gasped, and bit into my arm. But we never talked about it afterwards. Not to each other, or to anyone else.

We were friends — good ones, even — laughing at our own insular jokes, catching each other’s eye and, always, always, finding reasons to brush, caress, stroke any inch of skin. She was small and soft and smelt of spices I’d never heard of. When she grasped my forearm, her tiny fingers with their painted nails looked absurdly small, absurdly adorable. She’d always dig in, just a bit; never too hard, but hard enough that, later, I’d remember she’d been there.

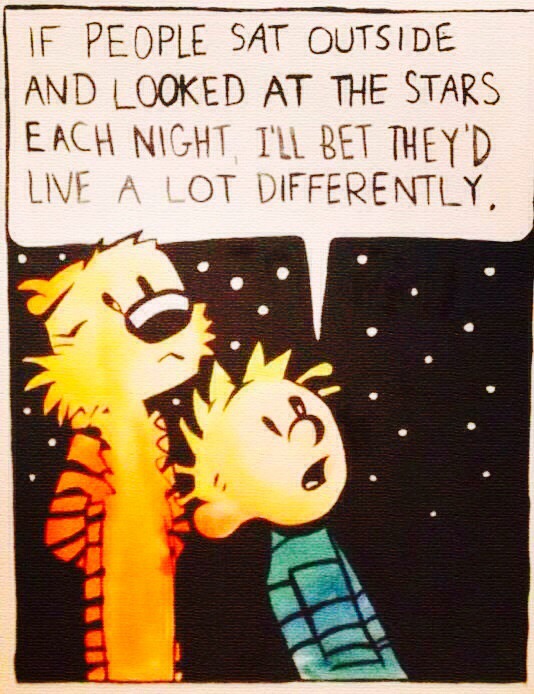

The hospital was near Lake Michigan, on Lakeshore Drive. I could see the lake from my window. The hospital, too. And, of course, the crumbling detritus of Uptown. The first time I’d walked in, seeing all those city lights sprawled out across the night sky, it’d taken my breath away. And it still did. Sometimes, because we were poor residents, they’d make us do twenty-four hour shifts, trying to squeeze as much labor out of our young bodies as they could. When she had one of those, I’d sit on the ledge by the window before turning in for the night, breathing in all of it: the lake breeze, the endless, darkling waters, and the flashing lights of yet another ambulance on its way to the ED.

Whenever I was at her place, we’d eat with one spoon, taking turns to feed each other a bite of buttered rice, or vanilla ice cream, wiping the excess from the corners of each other’s lips. What the hell were we doing? It was beautiful, in a way. After caring for so many patients, I guess, we just needed someone to care for us. I’d only eat halal so she’d bring up a plate of whitefish from the cafeteria, making sure I had something for sustenance. It was strange, really, watching our sense of self enlarge, ever so slightly, to envelope each other until it was second nature. She’d always leave little hearts on the sign-out for me, right next to my name. Two of them: one larger than the other. Was it an echo, or an affirmation? All I know is that I’d look down at those scribbles on long shifts and feel the stirrings of something I thought was lost long ago.

One night, she held her hands out to me, shyly, and asked me to paint them. I did; a thick, pink coat first, then — once it dried — a second, shiny lacquer. They sparkled where they caught the light from the lamp by the open window. She had an old guitar — a hand-me-down acoustic — and I dusted it off and tuned it and played it late into the night; sometimes badly, but, sometimes, the stars aligned in the room and out across the dark Midwestern sky where the aurora danced with no one to watch them and all I could do was lay back with my head in her lap, the heat from her browned thighs burning, burning bright.

In a couple of years we’ll be done with residency and tossed across the vast expanse of America like a handful of seeds from the pockets of a dilettante farmer. What‘ll be left, then, of these long days and longer nights? Memories, their edges softened and sepia-ed by time, glitter in the starlight. I’ll leave you with one:

Soon after a large lightning storm passed on, out over the lake, you called. Let’s go for a walk, you said. Wear something nice, you said. We walked down to Montrose Harbor, arm in arm, and sat on the rocks, feet dangling in the water, watching the birds and the boats come home for the night. On our way back, past the thick woods, I asked if you’d ever seen a firefly. You looked up at me and shook your long, dark hair; no, never. I held your bare, sun-kissed shoulders and spun you around to the deep woods. Look, there. Just pick a spot; don’t try too hard. And you did. That night, jaan, you saw the fireflies. I saw you.

Summer begins in Chicago, IL (2022)

Gharo, Sindh, Pakistan. PHOTO CREDITS: HASHAM MASOOD, M.B.B.S., BATCH XVIII

Gharo, Sindh, Pakistan. PHOTO CREDITS: HASHAM MASOOD, M.B.B.S., BATCH XVIII